Keep Scrolling Down for a Detailed Timeline!

1879-THE "INVISIBLE PRESENCE"

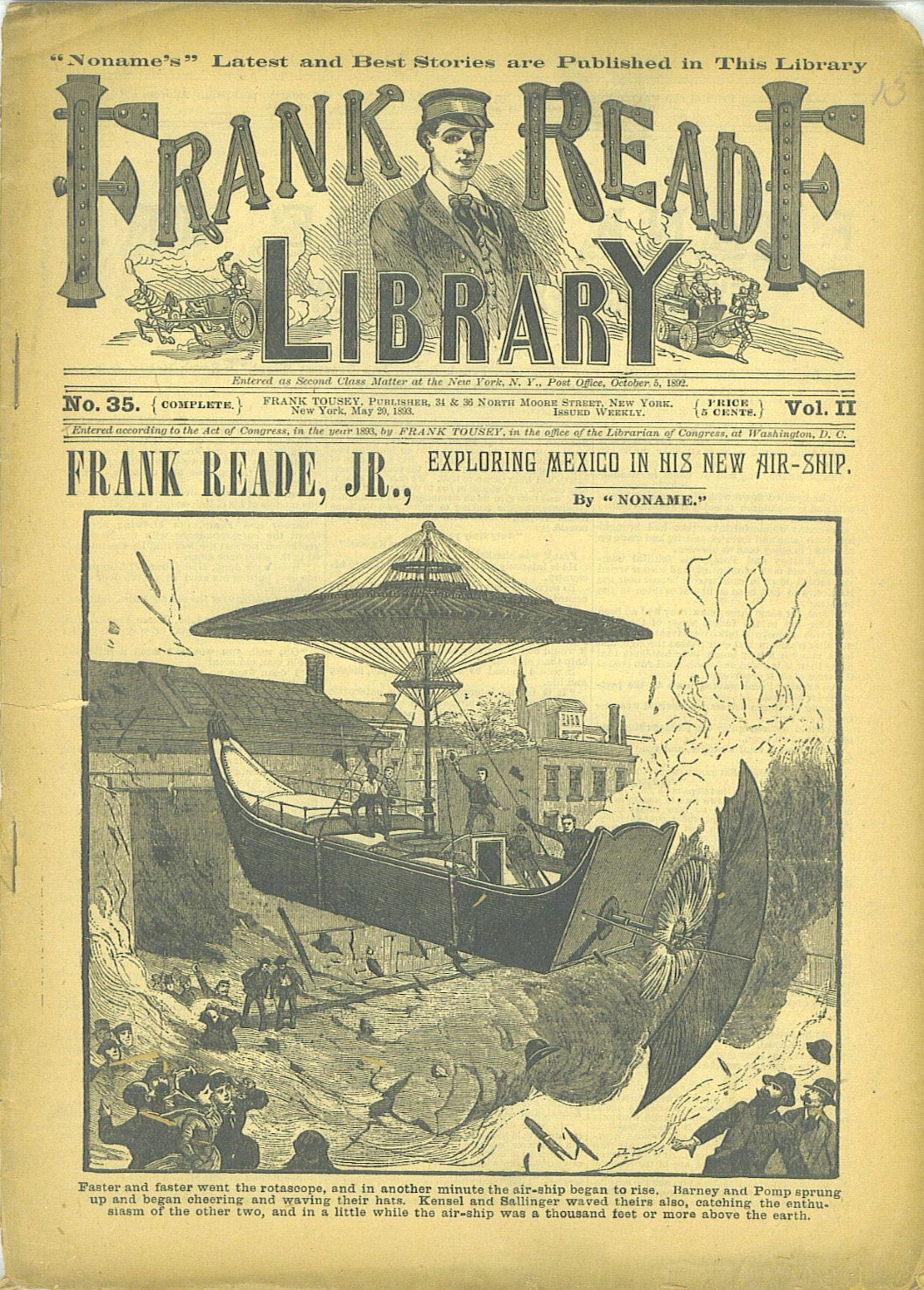

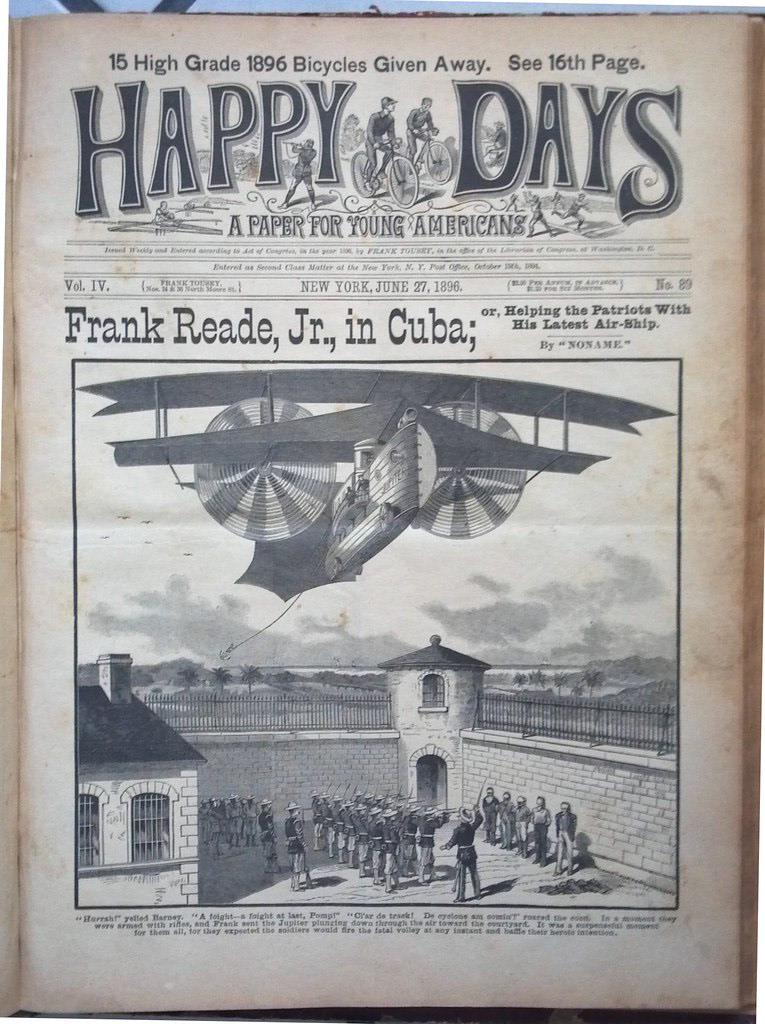

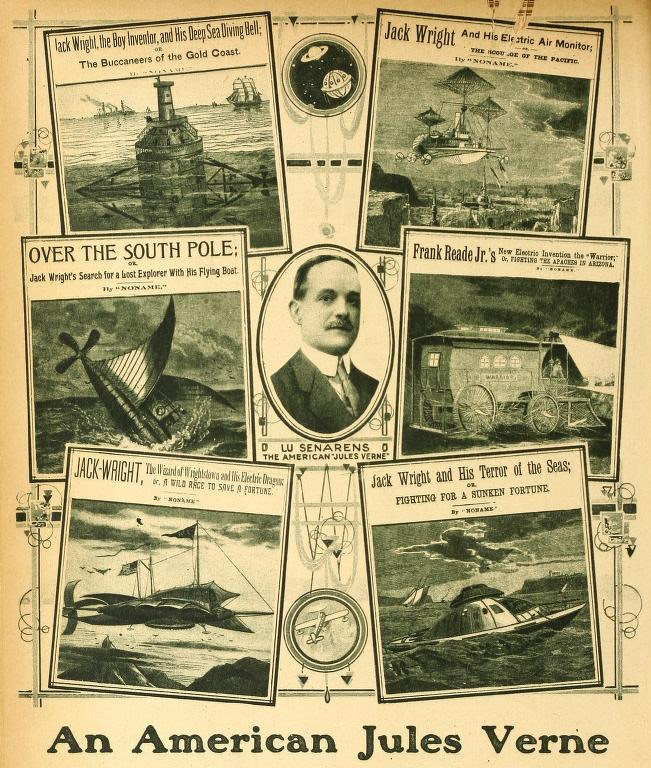

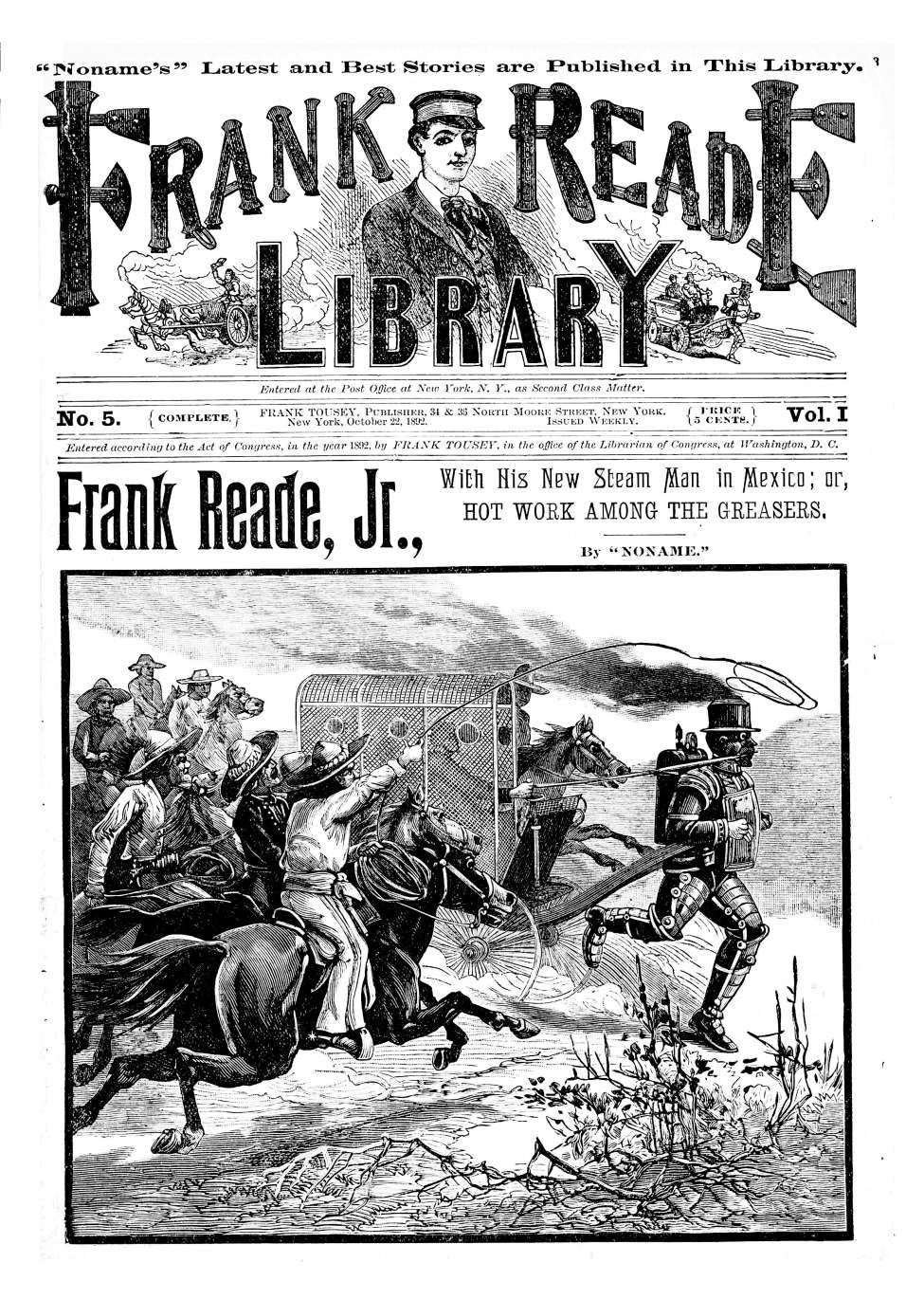

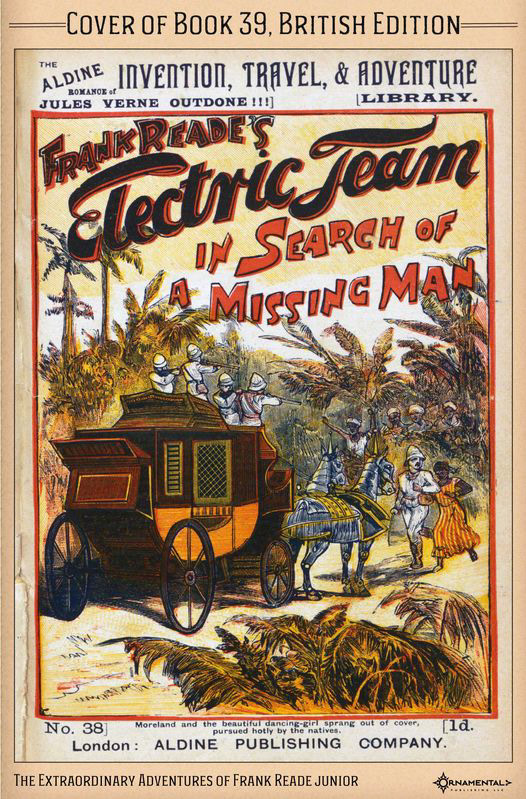

We can't know the first US Latinx science fiction writer. Instead, we can only wonder at an "invisible presence" that is only now being uncovered by scholars. The earliest known US Latinx sf writer is Luis Senerens, a Cuban-American from Brooklyn who wrote proto-sf dime novels of invention and exploration, works sometimes called "Edisonades" that precede sf. Ironically for our purpose of bringing more attention to Latinx sf, Senerens wrote not under his own name but under the pseudonym "No Name." As "No Name," he introduced the titular boy inventor of the novel Frank Reade Jr. and His Steam Wonder (1879) and wrote some 170 odd more titles in the series as well as more titles in a series about another boy inventor, Jack Wright. The inventions often involved transportation--airships, boats, dreadnoughts, even a rocket--and the stories traversed the world, sometimes discovering "lost races." Also ironic is the fact that they are deeply racist and imperialist. As the Encyclopedia of SF notes of Frank Reade Jr.: "As a whole, the sequence hints at the worst in the dime-novel tradition: very bad writing, sadism, a rancorous disparaging of all races with the exception of WASPS, factual ignorance, coarse Imperialist Clichés about Manifest Destiny and the right of the White Man to rule the world." Not in every way a great beginning. But as the ESF also points out, Senerens' works are central to the inventive Edisonade tradition that led to sf and to the creation of children's sf later, and he was certainly amazingly prolific. A 1920 retrospective of Senerens work dubbed him "An American Jules Verne" for the incredible size and scope of his work.

1940-INTERNATIONAL SF: "Reasoned Imagination"

International Latinx SF traditions influence US Latinx writers. Yet these traditions have often been unrecognized by US sf. Further, in their own countries, Latinx sf, like its US counterpart, often struggles for literary respectability. Frequently, Latinx sf is co-opted into the capacious "magical realist" label slapped on any non-realist Latinx literary work and so is simply ignored as sf.

The Argentinian writers and friends Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares provide an early instructive example of internationally famous Latinx works being undervalued as sf. Borges' imaginative fictions have been called "magical realist." Yet the sharp reasoning in his work, from the controlled approach to infinity in the strangely logical illogic of "The Library of Babel" to the estranging world-building of "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius," make one wonder what might be gained from a "sfnal" approach . Rachel Haywood Ferreira (The Emergence of Latin American Science Fiction, 2011) calls such reconsiderations of genre "retrolabelling," an important technique when the sf elements, long ignored, must be actively dug out to be understood aright.

In 1940, Bioy Casares published La invención de Morel (The Invention of Morel), in which a man escapes to an island where he discovers everything he sees and hears and senses is a recording by a machine invented by Morel. Borges wrote an introduction, calling it a work of 'reasoned imagination.' Goodwin and Stavans note: "his introduction...is seen as a classic statement of the significance of genre fiction." Borges connects Morel to H.G. Wells' and his "Scientific Romances," and, noting the absence of science fiction in earlier Latinx literature, hails Bioy Casares as the pioneer of a new genre. Borges is clearly open to and interested in the possibilities of genre work. His own work was sometimes translated into genre sf magazines, like a 1960 story that appeared first in Fantastic Universe. Borges edited an anthology with Bioy Casares and Silvina Ocampo, Antología de la literatura fantástica (1940), that encompasses excellent works of sf among its fantastic works. But despite all this, the promise of a new Latinx genre of the "reasoned imagination" remained muted by a market that insisted on the magical realism of all Latinx fantastic literature.

THE HIDDEN SF of EL MOVIMIENTO

El Movimiento, or the Chicano Movement, was a political and cultural movement in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s that sought to resist racism and forge a new, empowering Chicano identity. El Movimiento embraced artistic expression as a way to foster culture. Though largely unnoted, science fiction played a role. This is unsurprising because social activism and science fiction both dream of the future, imagining worlds that do not yet exist. Two notable sf works from the time are Californian Luis Valdez's "Los Vendidos" and Texan Reyes Cárdenas's "Los Pachucos Y La Flying Saucer." Both works are uproariously funny, charged with anarchic energy, using sf to challenge stereotypes from the inside. Neither is published in a genre outlet like a sf magazine or anthology

"Los Vendidos" is a one act play performed by Valdez's teatro campesino, the theater of the farmworkers that Cesar Chavez organized in the California grape strike and other actions. Goodwin and Stavans write of it: "Certainly one of the earliest works of Latino science fiction, although rarely interpreted as science fiction, ....first performed in East Los Angeles [at Elysium Park] in 1967. The story associates various stereotypes of Mexicans with different models of robots. In the end, the robots assert their resistance to being co-opted by then governor of California Ronald Reagan and so come together in solidarity."

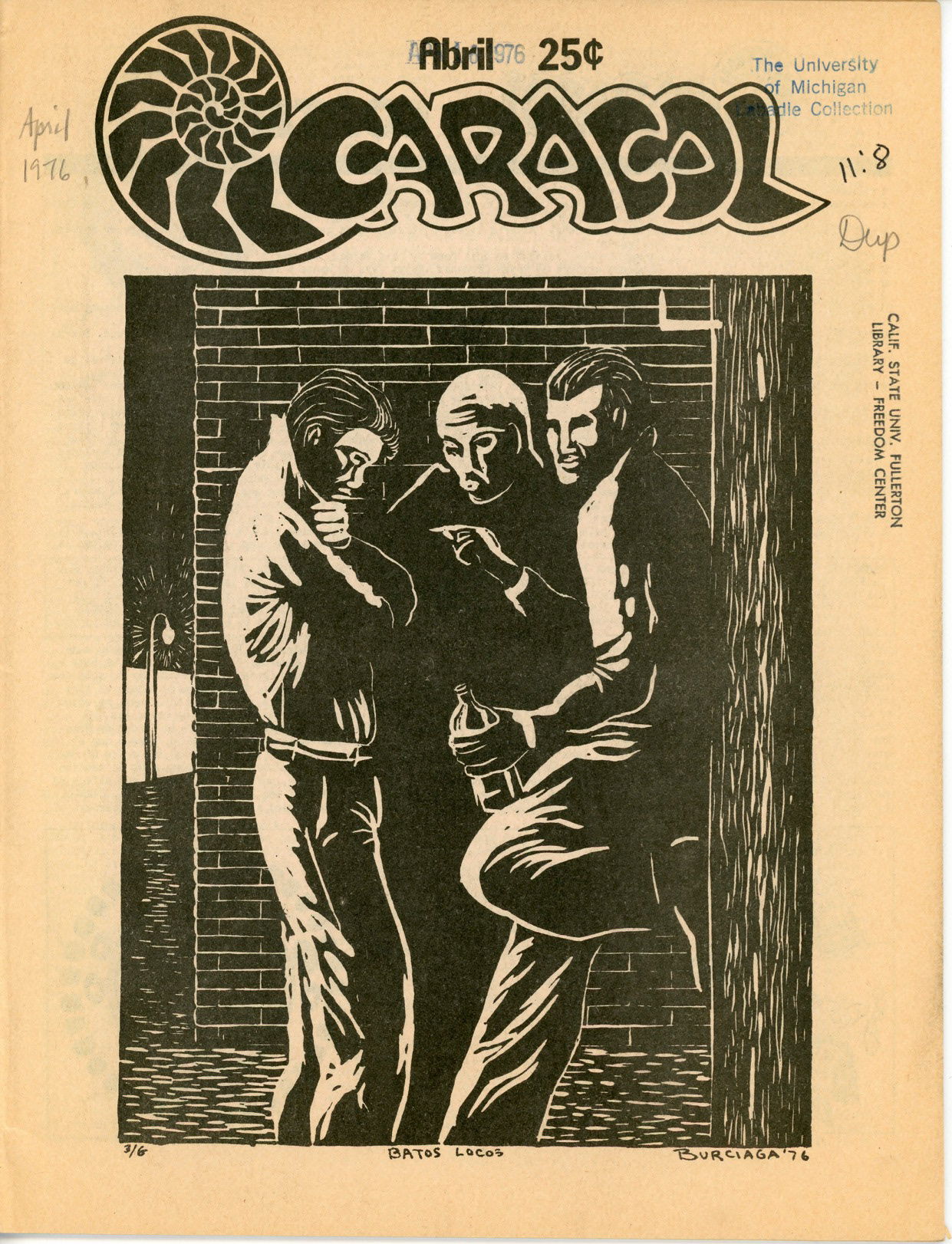

One of the stereotyped robots In Valdez's play is a pachuco, the zoot-suiters of the late 1930s and 1940s whose rebellious fashions and reclaiming of "Chicano" identity led the way toward El Movimento. In poet Reyes Cardenas' story, "Los Pachucos Y La Flying Saucer," two pachucos befriend a living flying saucer and take a trip through space and time, visiting key moments in Mexican and Chicano history from the Alamo to the Zoot Suit Riots. They lose and win and roll on, their unflagging riotous spirit seemingly the point of it all. They are unstoppable, constantly on the move into the new. Cárdenas' novella first appeared in Caracol, la revista de la raza, a Chicano literary magazine, in 1975, only republished again in his retrospective, Chicano Poet, 1970-2010 in 2013. The republished novella is five chapters long but Cal State Fullerton's Special Collections has in its holdings a "lost" sixth chapter from Cárdenas' groundbreaking sf work, as originally serialized in Caracol.

The Bladerunner Manuscript

CSUF's US Latinx Science Fiction Collection focuses on literature, but other story-telling mediums make an impact on the visibility and evolution of the genre. For example, Ridley Scott's iconic sf classic Bladerunner (1982), set in a rundown future LA, is not often thought of as Latinx sf. But Goodwin and Stavans write: "Relative to the history of science fiction, Bladerunner should be considered the most important science fiction film with a Latino sensibility. The original script of the film was written by a Chicano, Hampton Fancher, who added an important Chicano character who was then played by the most popular Chicano actor at the time, Edward James Olmos." The new character, Gaff, "was costumed as a futuristic Pachuco."

Also in Cal State Fullerton's Special Collections is an original draft of Bladerunner as written by Fancher alone, before Ridley Scott hired another writer, David Peoples, to revise.

LOVE and ROCKETS, Los Bros Hernandez

The influential comic LOVE and ROCKETS by Los Bros Hernandez is known for its groundbreaking alternative "underground" and queer sensibility. But as Shelley Streeby writes: "one of the most eye-catching elements was the comic's play with the icons of science fiction and fantasy." In particular, the stories of Jaime Hernandez, featuring Maggie the Mechanic who works on hovercars and rocketships as a high-tech Prosolar mechanic, make use of sf tropes. As Streeby writes: "Love and Rockets opened the door to a new wave of alternative comics that began to flourish in the wake of the Hernandez brothers' success. But...it is also important to see the comic as part of a constellation of Latina/o speculative fiction and speculative arts, which significantly distorts, denaturalizes, and thereby reimagines racialized hierarchies of space, race, genre, and sexuality....[T]he genres of science fiction and fantasy are not extraneous nor an obstacle to the more serious project of imagining nonnormative worlds, bodies, and ways of living that unsettle and transform hierarchies of gender, sexuality, class, and race in Southern California spaces....[T]he codes of SFF have always been and continue to be central to Jaime Hernandez's speculative fictions of alternate Chicano worlds, histories, and futures."

THE SCIENCE FICTION of GLORIA ANZULDÚA

Anzaldúa's ideas of the "nepantlera" (those existing in-between) and the emergent "mestiza consciousness" are fundamental to defining US Latinx SF. (If you have not yet read the "definition" section of this site, push the button below this entry or this link.) But that said--she has not been commonly thought of as a science fiction scholar. Her contribution is part of the "secret history" of US Latinx sf only now emerging. Instead, she has been read in the context of a number of disciplines to which her theories have been important, including Chicano/a studies, US postcolonial studies, women's studies, and queer studies. Yet her play on the slippage of the sf "alien" and the immigrant "alien" resonate in emergent US Latinx SF. And she borrows the early 20th-century idea (shorn of its alarming racism) of the sfnal "La Raza Cósmica" (the cosmic people) from early Mexican political philosopher Jose Vasconcelos. Also, she always looks forward, as when she writes: "En una pocas centurías, the future will belong to the mestiza." Her activism and her theory is about becoming and has always been "sfnal" whether readers noticed or not. She brings "science fiction thinking" to those who speak from the margins, drawing together, in fact, Latinx, postcolonial, feminist, and queer subjectivity with science fiction as a literature of liberation.

But it goes further: Anzaldúa wrote sf. As Susana Ramírez writes: "Many people familiar with Gloria Anzaldúa's work are unaware that she was an avid reader of science fiction and also wrote science fiction herself.

"In fact, one of her earliest drafts, variously titled 'Dreaming la Prieta' and 'Los Entremados de PQ,' dates to 1970, which makes her possibly the first Chican@ science fiction writer!"

Anzaldúa's science fiction includes: "Interface" (1987), which appeared in Borderlands/La Frontera, a narrative poem about courting an alien lover and taking it home to meet the family; "Werejaguar' (1991), unpublished, about interspecies subjectivity; "Puddles" (1992), from the anthology New Chicano/a Writing, an AIDS-era story of a future disease which brings new knowledge but leaves one shunned; and "Reading LP" (2009), published in The Gloria Anzaldúa Reader, the story of teleporting across time and space through the obsessive reading of a book--that is, through acquiring knowledge and acts of interpretation.

VOCA, the audiovisual archive at the University of Arizona Poetry Center offers recordings of Anzaldúa reading "Puddles" and "Interface" from 1991. (Just click the button above.)

The First US Latinx Science Fiction Novel

Ernest Hogan’s Cortez on Jupiter (1990), is the first Latinx sf novel published by mainstream US science fiction publishers, appearing in Ben Bova's "Discoveries" series for Tor. The novel did not sell well initially, remaining part of the "secret history" of US Latinx SF for another decade or more.

In a later Introduction, "The Secret Origin of Pablo Cortez," Hogan describes the process of selling the novel: "This is the Eighties. I did not sell Cortez on Jupiter as a Chicano science fiction novel. Nobody believed that there was an audience for such a thing." Initially, the novel "got great reviews. I was compared to William Gibson. I smiled a lot." But also: "Unfortunately, it didn't become a runaway bestseller. An editor at Tor called it a 'success d'esprit.'" It was not, clearly, a success in fact. But time passed and things changed: "now it is the 21st century, and tides are turning, we're hearing a lot about diversity, postcolonialism, Afrofuturism and nerds that come in colors--it may be Cortez on Jupiter's time had finally come.

I have this bad habit of being ahead of my time. Maybe that's why I became a science fiction writer."

Republished in 2014, here's what Publishers Weekly writes now: "Hogan's debut, first published in 1990, introduced the subgenre of Chicano SF to a startled, dazzled American audience.... All Pablo Cortez cares about is creating art, whether it's humongous graffiti sprayed across Los Angeles or zero-gravity paint slinging in space.... When he confronts the alien Sirens of Jupiter, who have zapped the minds of earlier explorers, he takes their overwhelming flood of bizarre images as subject matter for new masterpieces.... Hogan...builds a jangling, rambunctious picture of artistic genius. This is tons of fun for freethinking readers who appreciate heroes with cojones."

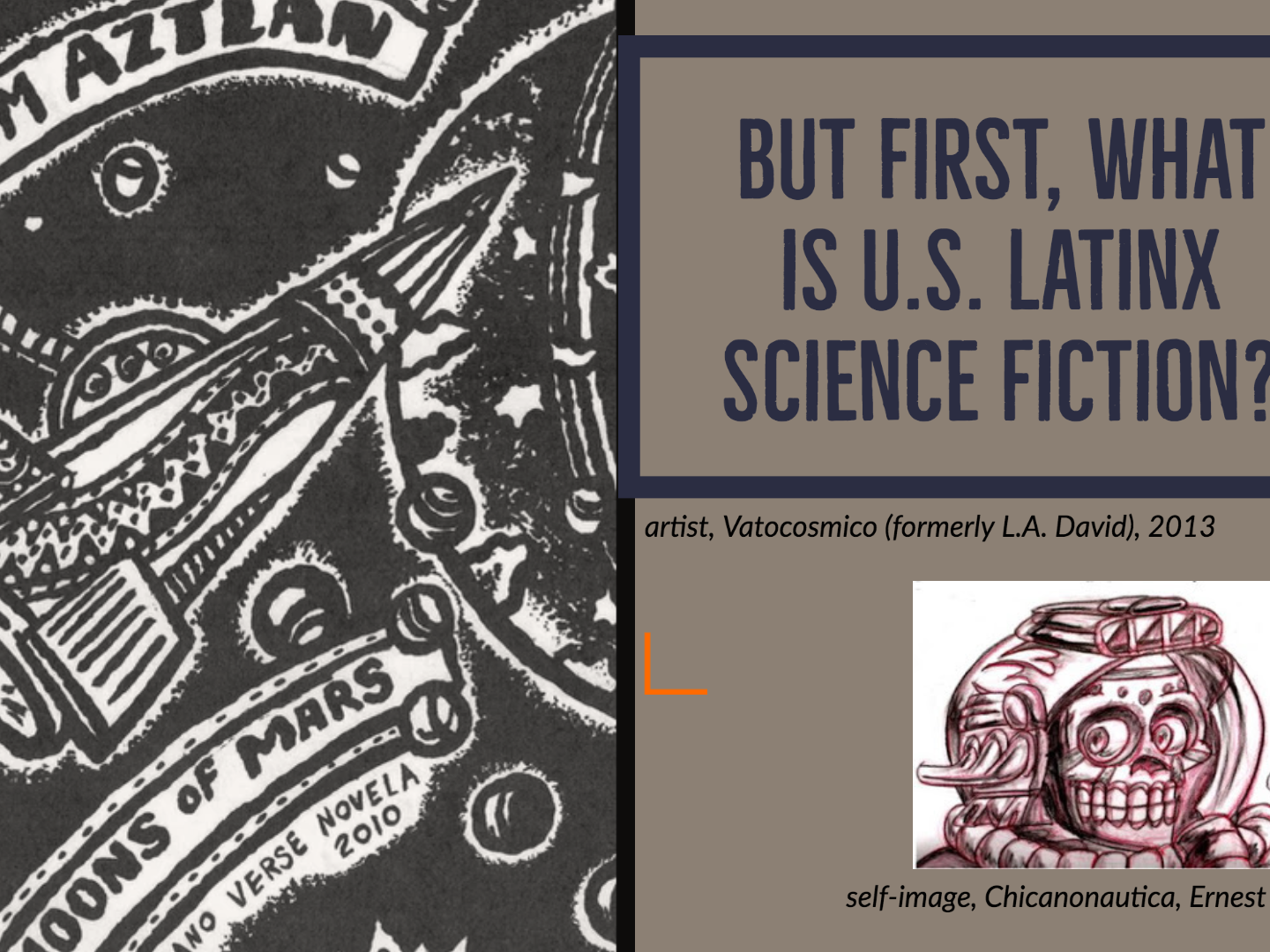

Hogan calls himself a "Chicanonautica" and wrote the "Chicanonautica Manifesto" in which he claims: "Chicano is a science fiction state of being. We exist between cultures, and our existence creates new cultures: rasquache mash-ups of what we experience across borders and in barrios all over the planet. As mestizos we have no sense of cultural purity. Mariachis on Mars? Seems natural to me."And: "I’m not interested in being puro Mexicano and only reaching the gente in the barrio. My roots embrace the planet, and reach out for the universe—the Intergalactic Barrio.

This is the time of Postcolonialism, Afrofuturism, and Chicanonautica.

We aren’t talking about an isolated, united movement. The virus is erupting all over the planet, in different forms, new recombinations. Look for it wherever people have new visions."

Where do we go from here?

What happens between the 1990 publication and 2014 republication to change the outlook on Hogan's novel and the value of "Chicano SF"? We will deal with Junot Díaz's Pulitzer-Prize-winning novel The Brief, Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (2007) in the next section, as well as the emergence of Latinxfuturisms in theory, art, and film, and the vocabulary they evolve to finally speak the "secret history" delineated here. But we must also note that Hogan's book is part of a steady if limited publication of US Latinx Science Fiction novels, pioneers all, that taken together turn "Nobody believed there was an audience for such a thing" into "the time of the "Chicanonautica" and other Latinxfuturisms.

Important works from this era that continue to draw critical attention now include Alejandro Morales's The Rag Doll Plagues (1991), Hogan's Smoking Mirror Blues (2001), Rosaura Sánchez and Beatrice Pita, Lunar Braceros, 2125-2148 (2009), Lawrence La Fountain-Stokes, Uñas Pintadas De Azul/Blue Fingernails (2009), Sabrina Vourvoulias, Ink (2012), and Paz Soldán, Iris (2014).

KEY WORKS CONSULTED for the “Secret History” and “Latinxfuturism” pages

Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera (1987).

Bell, Andrea L. and Yolanda Molina-Gavilán, editors and translators. Cosmos Latinos: An Anthology of Science Fiction from Latin America and Spain (2003).

González, Christopher. “Latino Sci-Fi: Cognition and Narrative Design in Alex Rivera’s Sleep Dealer.” Latinos and Narrative Media: Participation and Portrayal, Fredrick Luis Aldama, ed. (2013).

Goodwin, Matthew David. “Foreward.” Latinx Rising (2017).

---, “U.S. Latino Speculative Fiction,” subheading of “Speculative Fiction by Writers of Color,” Wikipedia.

Goodwin, Matthew David Goodwin, and Ilan Stavans, “Latino Science Fiction,” Oxford Bibliographies (2016).

Haywood Ferreira, Rachel. The Emergence of Latin American Science Fiction (2011).

Hernández, Robb, et al. Mundo Alternos: Art and Science Fiction in the Americas (2017).

Merla-Watson, Cathryn Josefina. “The Altermundos of Latin@futurism” (Alluvium, Vol 6, No. 1, 2017).

Merla-Watson, Cathryn Josefina, and B.V. Olguín, editors. Altermundos: Latin@ Speculative Literature, Film, and Popular Culture (2017).